Why significance matters to us

For us, both ‘significance’ and ‘interpretations’ are a bit of a category of their own. Whilst regular second-order concepts such as causation and change get pupils involved in history first-hand, significance and interpretations seem to do something different. These concepts allow us to take a step back and look at history being made, asking them to analyse the why and how in a ‘meta-historical’ way. This is an important part of classroom history as it encourages them to move away from seeing the past as ‘fixed’ facts and see history as a subject where varying claims to ‘truth’ are made.

Significance as degrees of importance

Although infamously difficult to pin down, we have started to find ways of thinking about significance that work for us and our pupils. Like others before, we have also rejected the idea of ‘significance’ as a fixed feature of particular aspects of the past and have instead focused on it being ‘ascribed.’ In the most recent Teaching History (190) there are some really helpful ways of approaching this; we especially recommend Worth’s exploration of how she has placed historians’ own accounts of the way they have ascribed significance at the forefront to illustrate how significance is relative. In the same edition, Card discusses how the extent to which some events of the past have been deemed significant have waxed and waned over the years.

We find thinking about significance in these terms really helpful. The extent to which things have/have not been seen as an important part of history and the reasons for this (such as Counsell’s criteria known as the ‘5 Rs) are fascinating points to explore. However, we also think there is something to consider in Brown and Woodcock’s point in their TH (143) article:

‘While this kind of analysis is important, only considering degree of significance would perhaps hide a more profound aspect to significance.’

What else is significance to us?

So, what else is there to explore?

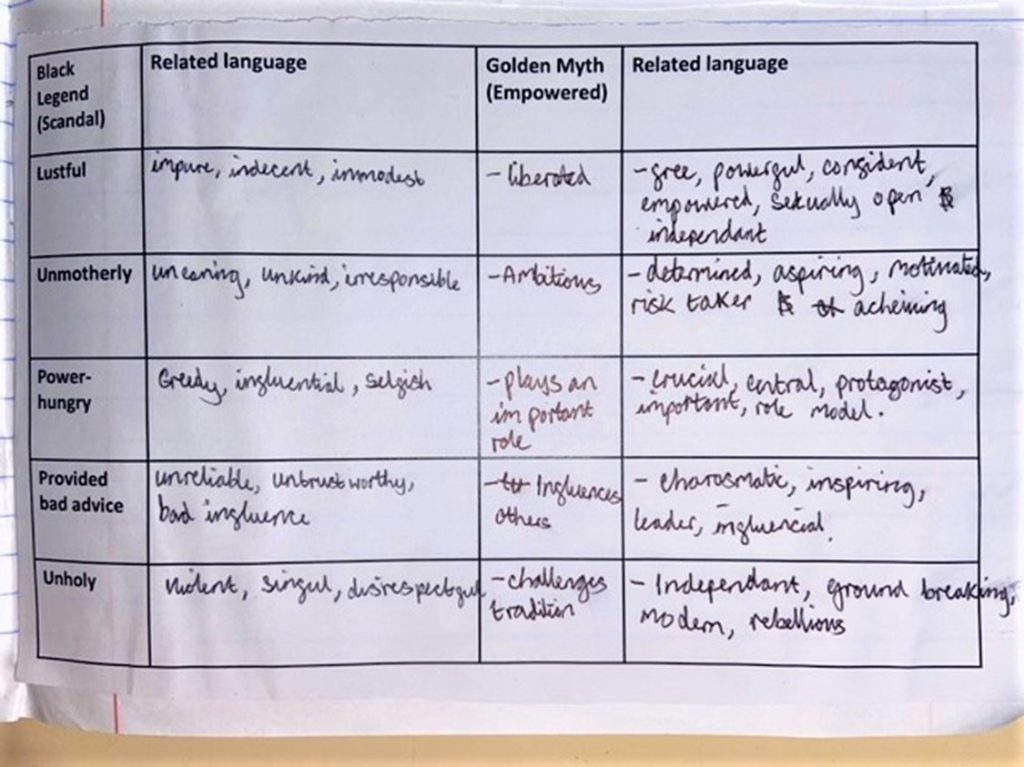

Rather than just looking at comparative extent of ‘weight’ and ‘importance’ given to aspects of the past, we have started exploring what one area symbolises to different people, a type of thinking about significance that cannot be characterised on a scale.

In other words, we are using ‘significance’ less as defined by Oxford languages as ‘the quality of being worthy of attention’ but rather by the secondary definition offered: ‘the meaning to be found in words and events.’ By following this approach, we are left to consider what different aspects of the past have signified to various individuals, movements, generations and groups. To do this we can explore the local, temporal or personal concerns that have affected the way in which something is remembered. We might find an aspect or individual from the past to be celebrated, criticised, manipulated, distorted, accentuated, diminished or presented in any other way imaginable for all manner of complex reasons. The way we have been experimenting with significance, is therefore not a question of ‘significant or not’ but a question of ‘signifier of what.’

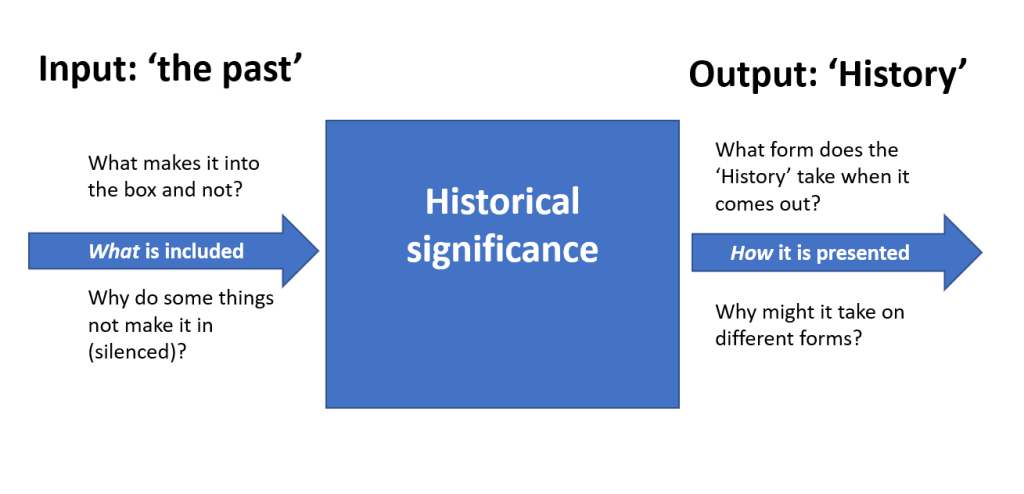

The ‘mysterious box’ of significance

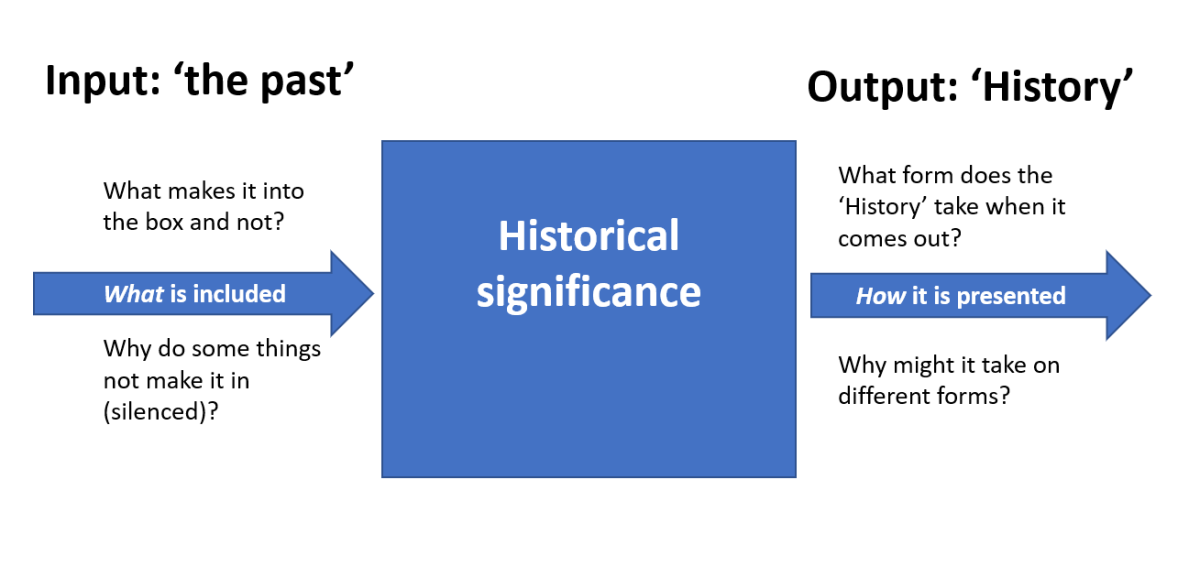

‘Historical significance’ is, like interpretations, about exploring how history is made. It is the mysterious process of the production of history that we want our pupils to explore and analyse.

We have played around with a number of analogies but none did the process justice. Instead, we settled on the idea of a ‘mysterious box’ into which the past enters and is transformed into ‘history.’ We started to see this as a two-step process:

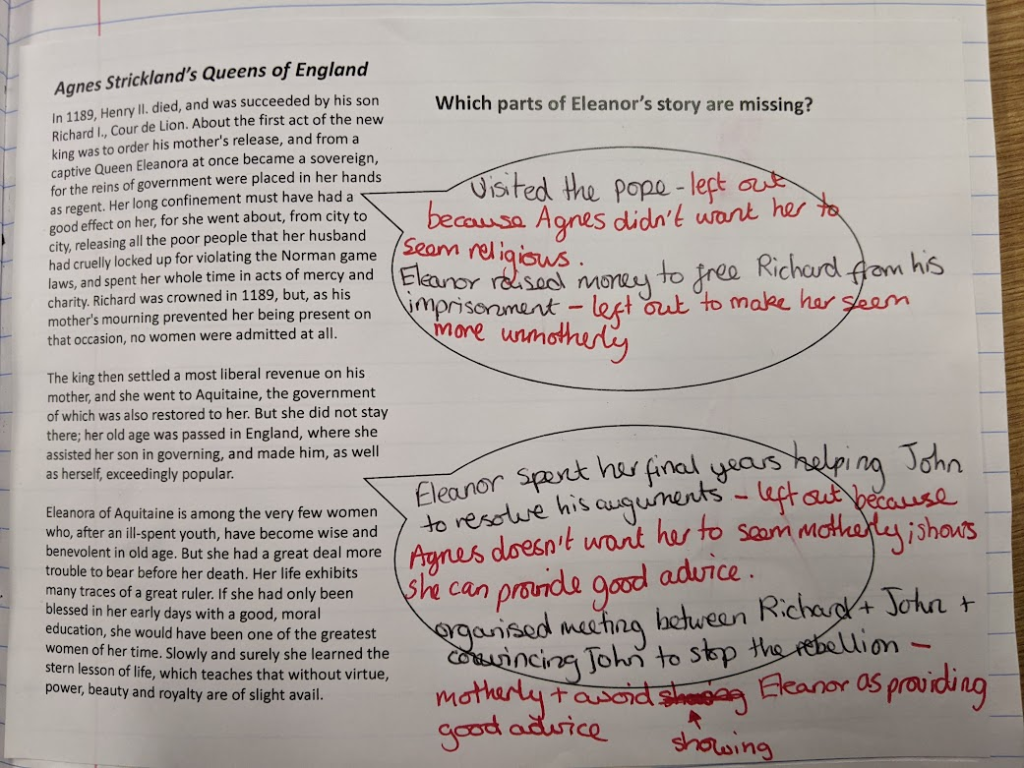

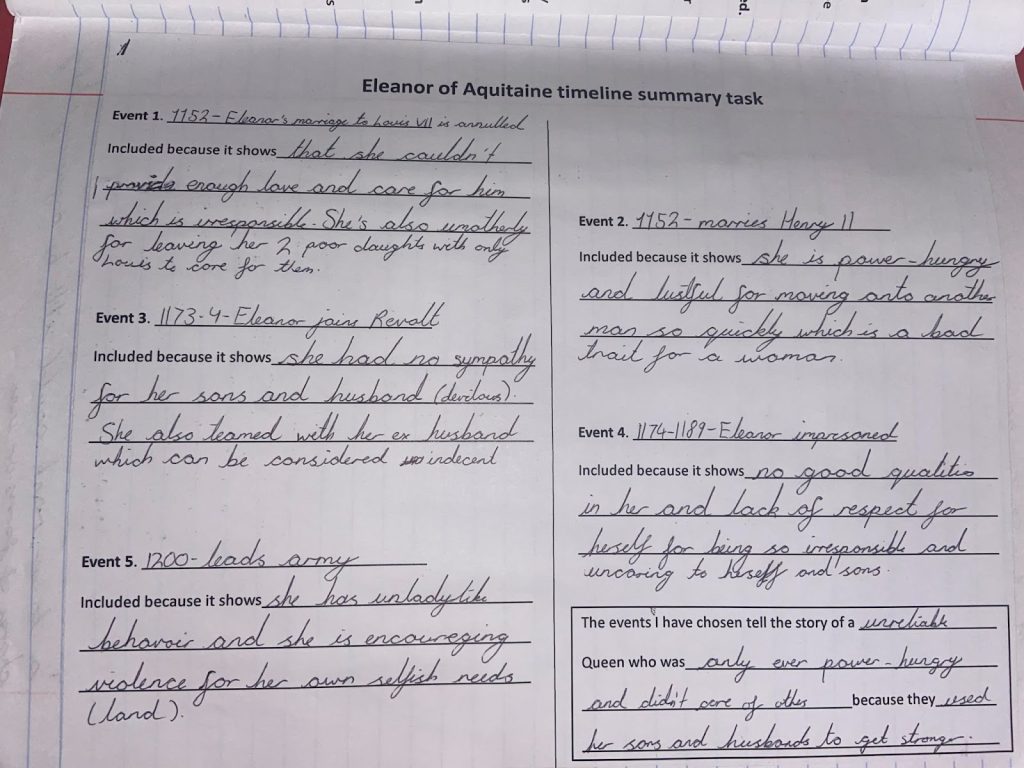

1) What bits of the past make it into the box in order to be processed into history and why? This is the well-theorised aspect of significance, dealing with comparative ‘importance’, ‘weight’ and ‘silences’ in the past.

2) What form does this aspect of the past take on when it has been through the process and comes out the other side as history? And how do different representations of the same aspect of the past go through the process and emerge looking so different? This is the less theorised part we’ve been experimenting with. We think there are lots of exciting opportunities here for pupils to explore the impact of the archive, archivists, historians and wider creators of History on the form the past becomes.

But why is the process within the box ‘mysterious’? One reason is that it is not directly visible to us. The different influences on the historians as they make the past into their own version of history and many and varied. It takes a lot of unpicking to see how these different forces work together to create the outcome.

Another reason it is mysterious is that the manufacturing of past into history is not the work of professional historians alone. It might also involve popular memory which often doesn’t have a standard set of methodologies, such as making claims from a range of evidence, which makes the challenges of understanding the process even greater for pupils. There is not always a set process that significance can be boiled down to as each area under investigation is unique to the particular circumstances and events of each of society. This makes the exploration of what happens when the past is becoming history all the more mysterious and intriguing….

How could this translate into the classroom?

| Enquiries centred on the input (weight and inclusion) | Enquiries centred on the output (different representations) |

| Why have the voices of X been silenced? | How has X been constructed/ invented? |

| Why have historians included X in their stories about Y? | How has the history of X been rewritten? |

| Why has the topic of X recently become of interest to Y? | Why has X been remembered so differently? |

| Why do X still care about Y? | Why has X become a symbol of opposing histories? |

| Why do X present the Y so positively? |

Our enquiry: How can Thanksgiving be a symbol of such opposing histories?

Rationale for the enquiry

Our pupils study the Making of America paper (1789-1900) at GCSE and we have always been painfully aware of the lack of knowledge pupils have about life in America before 1789. Our department philosophy is that pupils should encounter those colonised only after they have encountered a group before colonialism and so we currently do this with a unit entitled ‘How useful is the term Native American?’ This year we decided that to fully prepare our pupils with the background knowledge about Native and white relationships which gets picked up by our GCSE course, it would be really helpful for pupils to have a better understanding of the Early encounters between Native Americans and European settlers.

We were particularly inspired by the talk giving at the last HA conference by the new Hodder textbook team and particularly by Tom Allen where he introduced us to David Silverman’s book: This Land Is Their Land: The Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Colony, and the Troubled History of Thanksgiving. In the introduction to this book, Silverman asserts:

“The Thanksgiving myth promotes the idea that this event involved Indians gifting their country bloodlessly to Europeans and their descendants to launch the United States as a great Christian, democratic, family-centred nation blessed by God’.

We thought it would be really interesting to explore how divergent views of this event could have come to exist. We have always looked from a European-focused perspective at the Pilgrim Fathers when we explore the consequences of the Protestant Reformation in Year 8 so we thought it would be really important to try and challenge this perspective.

Outline of the enquiry

| Lesson Question | Content covered | Aspect of significance developed |

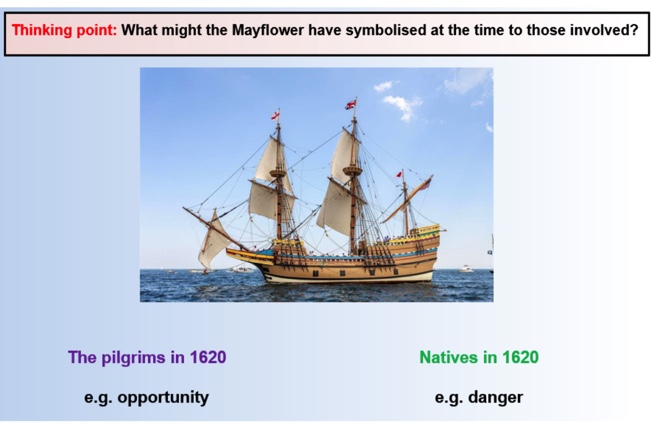

| Lesson 1: What role do early encounters between Europeans and Natives play in how Thanksgiving is remembered? | Traditional myth of Thanksgiving – the celebratory version given to young children in America Story of early encounters between Native Americans and White Americans (e.g. epidemic of 1616-1619) up to the Mayflower landing. | What might the Mayflower have symbolised to those white Americans and Native (Wampanoag) Americans at the time? |

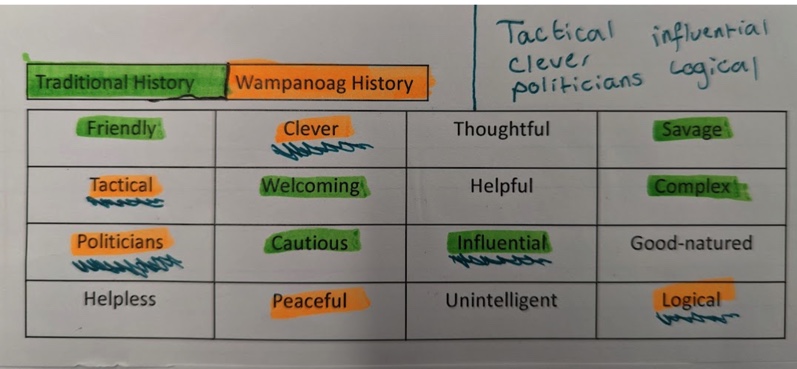

| Lesson 2: What role does Massasoit’s story play in how Thanksgiving is remembered? | The story of the creation of Plymouth Colony Wampanoag and Pilgrim Fathers’ temporary alliance Events of original ‘Thanksgiving’ | How was Massasoit viewed by… the English settlers at the time (using sources from the period) and also Native oral accounts of who Massasoit was. How do these contribute to opposing stories? |

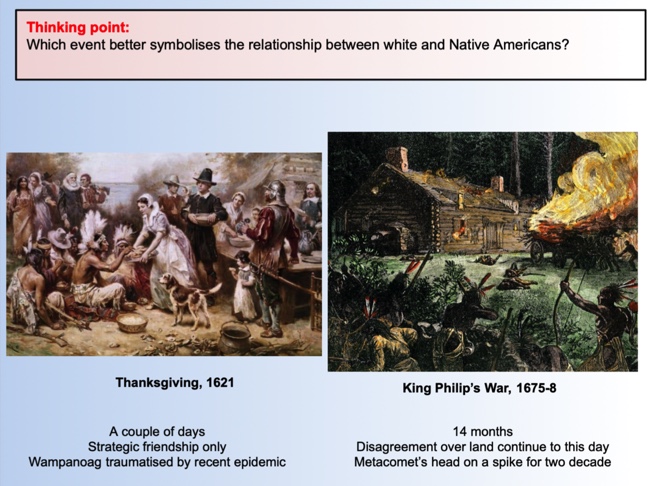

| Lesson 3: What role does the story of King Philip’s War play in how Thanksgiving is remembered? | Relationships after Massasoit’s death leading to King Philip’s War 1675-1676 | How including contextualisation of Thanksgiving with negative relations following changes its overall impression. Pupils question which event better symbolises the relationship between white and Native (Wampanoag) Americans – King Philip’s War or Thanksgiving? Pupils also think about the nature of the source record available and how this might have influenced what has been remembered (including Native wampum belts) |

| Lesson 4: How can Thanksgiving be a symbol of such opposing histories? | Pupils look at the Native American version of Thanksgiving as the Day of Mourning (created by Frank James in 1970) by looking at an overview timeline of settler-colonialism in America from 1676-1900. Pupils explore how Native ideas about identity, gender and nation were eroded through land acquisition and other processes such as putting young children into boarding schools. | Pupils explore why an overview of destruction of Native culture changes the light in which Thanksgiving can be remembered. Why would these two groups want to tell such different stories about the conception of America? Is Thanksgiving (in isolation) representative of the beginning of America? |

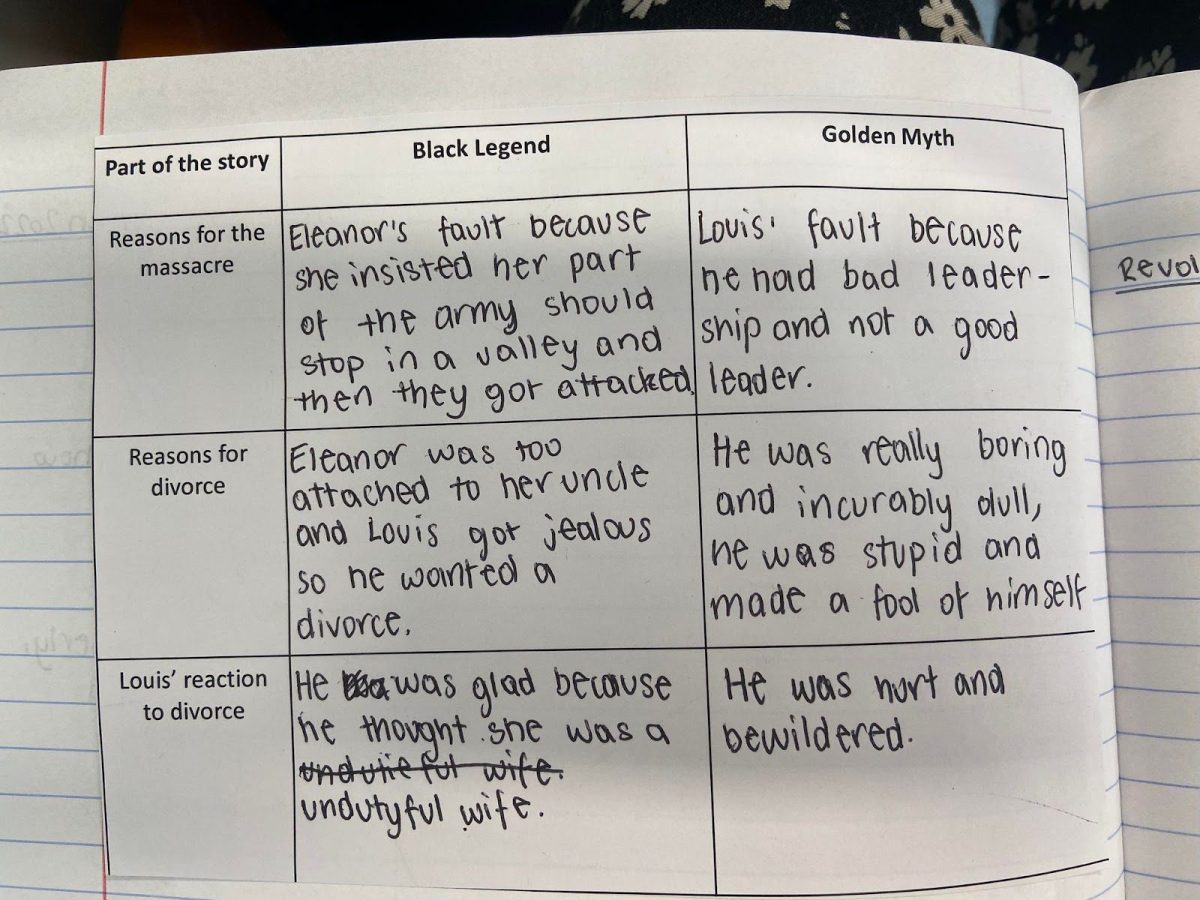

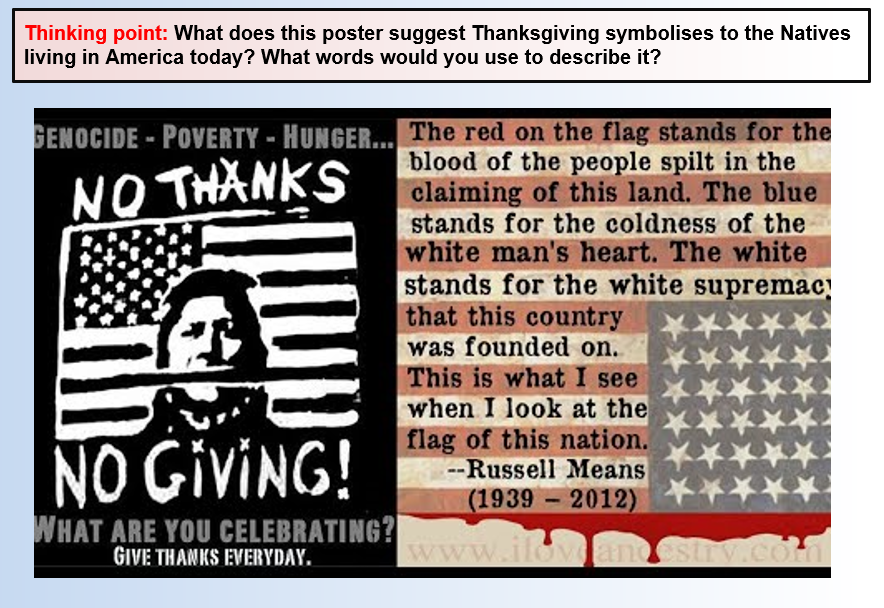

Building up a sense of two versions of History

At the heart of this enquiry was ensuring that pupils were clear on the fact that different versions of ‘Thanksgiving’ clearly existed. Pupils were initially exposed to the traditional sanitised version of the ‘holiday’ story to build on any general awareness they had about the event already.

However, we then contrasted this image with ‘National Day of Mourning’, which was the name given to Thanksgiving, by a Native American, Frank James in 1970, saying:

“This is a time of celebration for you – celebrating an anniversary of a beginning for the white man in America. A time of looking back, of reflection. It is with a heavy heart that I look back upon what happened to my People.’

This powerful speech contrasts so vividly with the traditional story of Thanksgiving that it shows the different ‘outputs’ and representations that get created very clearly. Also helpful in this was the opportunity to explore the nature of the language that was used in both ‘versions’ of how Thanksgiving has been presented. This supported pupils in getting to grips with the wider ideas and meanings of both representations.

Symbols: a way into thinking about the mysterious box

One way we introduced pupils to what might go on inside the ‘mysterious box’ is by getting them to think about what the same aspect of the past could have represented to both the white settlers and the Wampanoag. This was to highlight that the making of history involves agency and decision making: both what and how you might remember something might vary depending on the impact that it has on you and your community. We hoped that this engagement with human emotion and the role of the present in understanding the past would open up pupils’ understanding of why events could represent opposing things to different people.

Events as representations

Of course, the selection of different aspects of the past (input to historical process) cannot be totally separated from the form the end product takes (output of historical process). As Trouillot explores in his work Silencing the Past, archives, archivists, historians and public memory can affect what parts of history are emphasised and left out. What is typically explored in the classroom is the reasons for these inclusions and omissions. What we were especially interested in however is how said inclusions and omissions create certain impressions in the wider representations.

For instance, in the context of our Thanksgiving enquiry, it is notable that the traditional telling of Thanksgiving zooms in on a few days of particularly harmonious relations between the settlers and the Wampanoag. By filtering out negative relations prior to Thanksgiving and the deterioration of relations after, the traditional narrative ends up taking a more celebratory and peaceful tone of America’s conception. Conversely, these filtered out aspects of the past hold a more powerful place in Wampanoag collective memory, meaning they might perceive the conflict of King Philips’ War as perhaps more emblematic of the story. Even more so, when it is viewed from the perspective of the longer-term destruction of Native identity and culture over the following centuries. By emphasising, contextualising, filtering and highlighting different aspects of the same story, very different versions of history can therefore come to light.

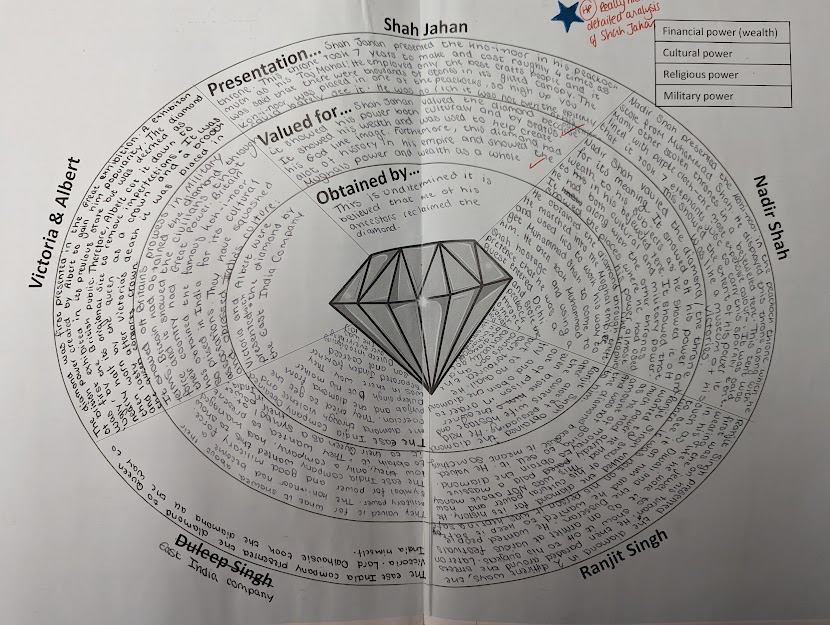

Sources and the form of History

One way we got pupils to focus on what happens in the ‘mysterious box’ was by looking at the role of the evidential material in the representations of history created. We explored this in Lesson 2 when we looked at the story of Massasoit, the chief sachem of the Wampanoags. He worked in an alliance with the Pilgrim Fathers, leading to the events that have become known as Thanksgiving. Pupils explored original sources produced by the Mayflower passengers and considered how these could have contributed to the traditional sanitised version of Thanksgiving. Then, pupils contrasted this with Wampanoag oral accounts of Massasoit. This micro-level exploration of differences in the source record itself allowed pupils to see how different versions of history were shaped from the moment they occurred.

In his person he is a very lusty man, in his best years, an able body, grave of countenance, and spare of speech. In his attire little or nothing differing from the rest of his followers, only in a great chain of white bone beads about his neck, and at it behind his neck hangs a little bag of tobacco, which he drank and gave us to drink; his face was painted with a sad red like murry, and oiled both head and face, that he looked greasily. All his followers likewise, were in their faces, in part or in whole painted, some black, some red, some yellow, and some white, some with crosses, and other antic works; some had skins on them, and some naked, all strong, tall, all men of appearance . . . [he] had in his bosom hanging in a string, a great long knife; he marvelled much at our trumpet, and some of his men would sound it as well as they could.

Mayflower passenger Edward Winslow described Massasoit in Mourt’s relations, 1622

Pupil outcome work

To many people, Thanksgiving is seen as a time of celebration because, in the traditional story, the Native Americans helped the Pilgrims and they ate a feast together as friends. Many events before and after the meal were filtered out, and the emphasis is put on the Native Americans and the Pilgrims eating together in peace. All the sources that got recorded were by the European settlers, who wanted to make it seem like they did nothing wrong. These biased records presented the Native Americans as wild and uncivilised because the settlers wanted to justify their hostility towards them and show that they had the supposed right to be in charge of America. Many people want the start of America to be remembered as a peaceful time which started off with a friendship between the Europeans and the Native Americans whereas, in reality, it started with lots of conflict and death.

To many people, Thanksgiving is seen as symbol of mourning because it marks the start of the conflict of King Philip’s war, which was responsible for the deaths of many Native Americans. When the traditional events are put into context then it shows that, in reality, the friendship between the Native Americans and Pilgrims only lasted for a few days. For example, in the years leading up to 1620, there was a deadly epidemic brought over by French traders that wiped out many in the Wampanoag nation. This created mistrust between the Wampanoag and the new settlers because they were worried that a similar event would happen again. When the Pilgrims came over in 1620, they stole all the Wampanoag’s food supplies and tried to take their land. Later, after Thanksgiving, the Pilgrims started taking more land, forcing their laws onto the Native Americans. This created tension because the European settlers were taking all the resources and trying to take power away from the Wampanoag. Soon, a war broke out which led to many Native Americans being killed and the remaining Natives being sent to ‘reservations’. The children were sent to Christian boarding schools where they were lied to about their history and forced to abandon their identities and beliefs. Many of the Native American perspectives were lost because they were not recorded – apart from on a few surviving wampum belts, which told the story of what really happened. Because so many of the records were written by the Pilgrims, key events in the true story were left out.

Conclusion: Thanksgiving can be seen as a symbol of such opposing histories because many of the original events were filtered out by the European settlers. It wasn’t the start of

America as it is seen today, but the end of thousands of years of Native Americans living there peacefully with the land. The settlers were barbaric towards the Native Americans, and

Thanksgiving should be remembered as a tragic event which was the cause of many deaths instead of a time of peace and friendship.