Two history teachers from Cambridge sharing ideas, interests and curricular work

Reading in the History classroom: why, what and how?

Why read with our pupils at all?

It is a struggle to put into words just how important reading is in pupils’ everyday lives and for success in our subject. Keith Stanovich uses the phrase ‘the Matthew Effect’ to describe the way in which early exposure to reading usually leads to faster progress later in education, as it enables pupils to comprehend and work out new vocabulary more easily. As such, the vocabulary gap between weaker and stronger readers grows as the ‘rich get richer and the poor get poorer’. This often manifests in History classrooms where some pupils already have rich mental pictures when you ask them about complex vocabulary. However, as rich vocabulary is so core to the discipline of History, thinking about what and how to read is not just a pedagogical issue, it is an issue of accessibility in our subject. This is a social justice issue: there is a proven link between poverty and social disadvantage and low levels of literacy. By the age of 15, 55% of non-FSM students have a reading age of 15 or more compared to only 44% of FSM students.

By Sarah Jackson-Buckley

read moreHistorical significance: the concept that is hard to pin down!

Why significance matters to us

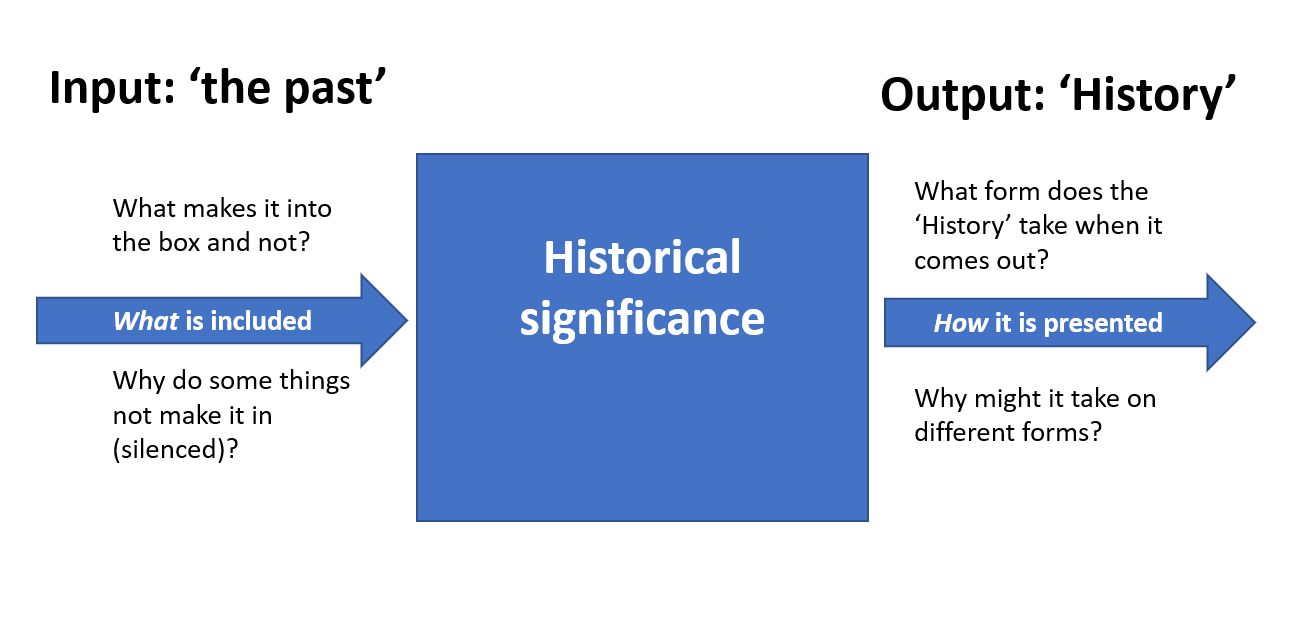

For us, both ‘significance’ and ‘interpretations’ are a bit of a category of their own. Whilst regular second-order concepts such as causation and change get pupils involved in history first-hand, significance and interpretations seem to do something different. These concepts allow us to take a step back and look at history being made, asking them to analyse the why and how in a ‘meta-historical’ way. This is an important part of classroom history as it encourages them to move away from seeing the past as ‘fixed’ facts and see history as a subject where varying claims to ‘truth’ are made.

By Sarah Jackson-Buckley

read morePower in India through material culture: how we have used the story of the Koh-i-Noor diamond to explore imperial rule

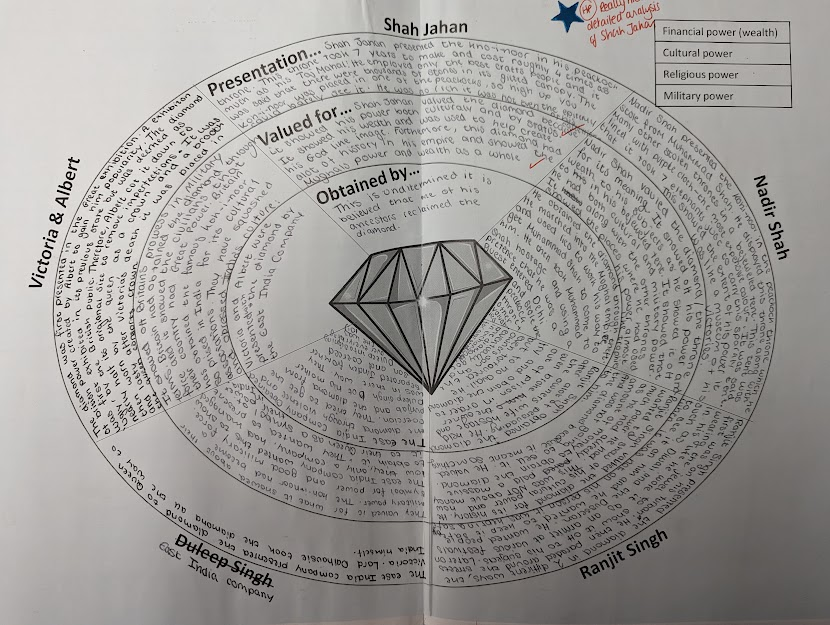

Of all the examples of colonial loot, the Koh-i-Noor diamond is one of the most controversial. The recent decision to avoid using it in the upcoming coronation ceremony seems a sensible one considering the many disagreements and competing claims over its past and future. The question we wanted to explore with our Year 9s is: how has one stone come to symbolise so many things over the centuries?

By tracking the diamond through the ages as it is dramatically passed from empire to empire, we can observe how the cultural value of the Koh-i-Noor grows and evolves. We can extract lessons about the use and display of power and how an object is afforded its value through what it comes to represent. Even though the story is one told at overview level, we can gain a real depth of knowledge about the empires of the Indian subcontinent and the nature of British colonial rule. As a result, the story is full of opportunities to incorporate aspects of decolonial thinking in authentic and challenging ways.

By Sarah Jackson-Buckley

read moreInventing Eleanor: how historians’ re-imaginings of Eleanor of Aquitaine helped our Year 7s understand how historians work

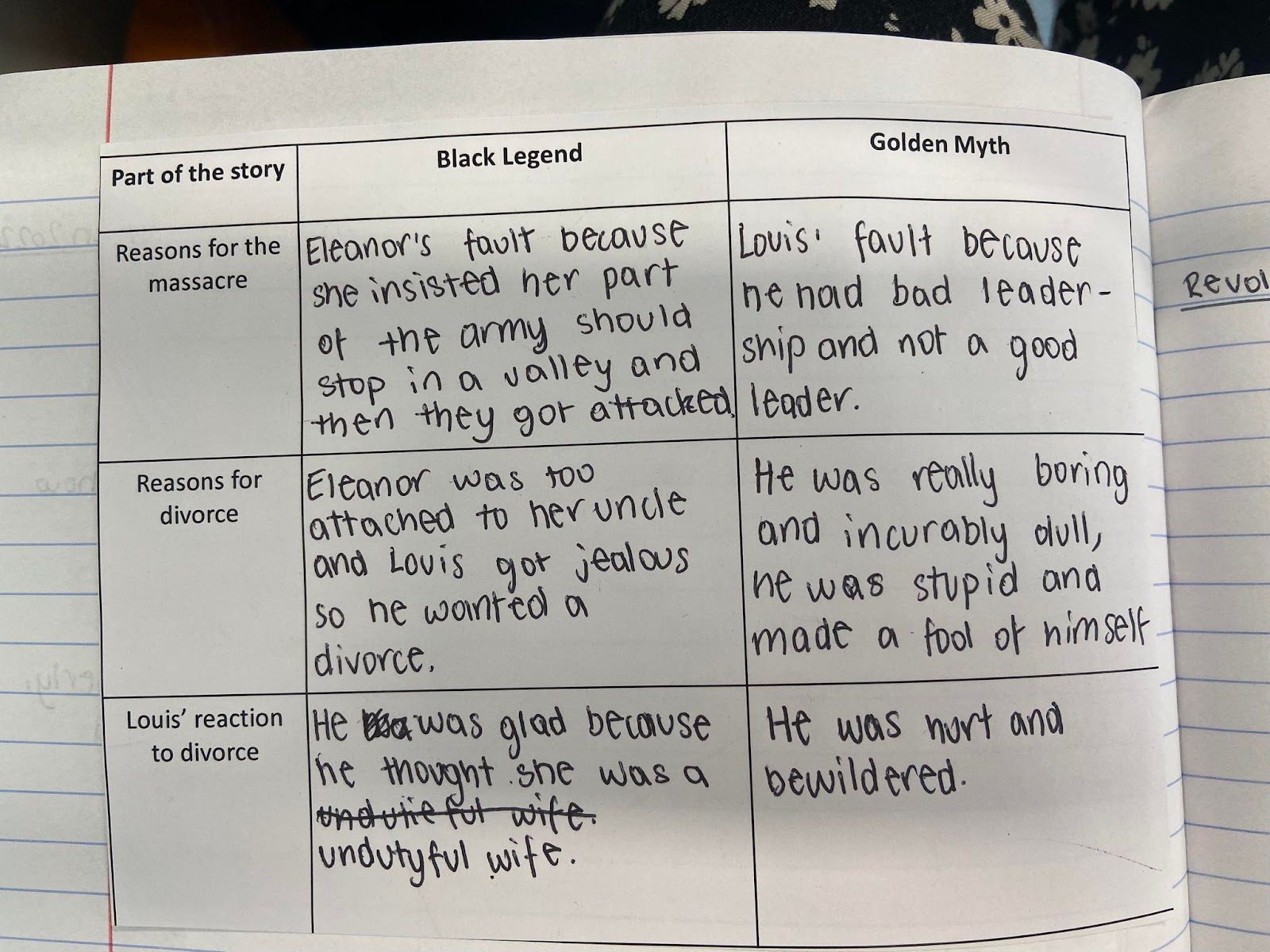

This year we approached our Eleanor of Aquitaine enquiry differently. We focused on what Eleanor’s story has represented to different historians, and why she has therefore been presented in different ways. In doing so, we asked the question of how Eleanor’s story and character has been ‘invented’, a term which encapsulates the idea that historians are active creators of new content in their work.

As is often the case, the enquiry straddles the divide between significance and interpretations. The concept of significance shone through in pupils’ exploration of how the historians select and emphasise different aspects of the past within Eleanor’s story according to their values and interests. As such, these historians determined which parts of Eleanor’s story left the realm of the ‘past’ and entered historical consciousness. The different parts of Eleanor’s life historians featured resulted in different ‘versions’ of Eleanor being remembered. As such, the enquiry demonstrates how significance works in a disciplinary context.

By Sarah Jackson-Buckley

read more