Of all the examples of colonial loot, the Koh-i-Noor diamond is one of the most controversial. The recent decision to avoid using it in the upcoming coronation ceremony seems a sensible one considering the many disagreements and competing claims over its past and future. The question we wanted to explore with our Year 9s is: how has one stone come to symbolise so many things over the centuries?

By tracking the diamond through the ages as it is dramatically passed from empire to empire, we can observe how the cultural value of the Koh-i-Noor grows and evolves. We can extract lessons about the use and display of power and how an object is afforded its value through what it comes to represent. Even though the story is one told at overview level, we can gain a real depth of knowledge about the empires of the Indian subcontinent and the nature of British colonial rule. As a result, the story is full of opportunities to incorporate aspects of decolonial thinking in authentic and challenging ways.

In this short blog post, we hope to show how we went about exploring this unbelievable story and perhaps to inspire others to incorporate the powerful history of the Koh-i-Noor into their own teaching.

EQ: What does the Koh-i-Noor reveal about the power of its possessors?

| Lesson question | Content covered | Sources used to construct the cultural ‘meaning’ of the diamond through the ages. |

| Lesson 1: What does the Koh-i-Noor reveal about the power of the Early Mughals? | Humayun (Mughal Emperor) and Shah Tahmasp (Ruler of Persia). | |

| Lesson 2: What does the Koh-i-Noor reveal about the power of Shah Jahan? | Shah Jahan and the Mughal Empire. | Close analysis of Peacock Throne. |

| Lesson 3: What does the Koh-i-Noor reveal about the power of Nader Shah? | Nader Shah and the Persian Empire. | Contemporary description of Nader Shah. Comparison of Mughal Peacock Throne and Nader Shah’s Peacock Throne and armband. |

| Lesson 4: What does the Koh-i-Noor reveal about the power of Ranjit Singh? | Ranjit Singh and the founding of the Sikh Empire | Close analysis of a source from a courtier who wrote about the display of the diamond. |

| Lesson 5: What does the Koh-i-Noor reveal about the power of the East India Company? | Story of Duleep Singh and the growth of the East India Company. | Lord Dalhousie’s comments after getting the Koh-i-Noor |

| Lesson 6: What does the Koh-i-Noor reveal about the power of the British? | Story of the diamond’s journey to England, its recutting and the Great Exhibition, its presentation by Queen Victoria to Duleep Singh and Duleep’s Singh troubled life. | Close focus on the difference between the diamond before and after cutting |

The Koh-i-Noor’s story

The Koh-i-Noor by William Dalrymple and Anita Anand is one of the most page-turning history books we have come across. The first half, written by Dalrymple, focuses on the diamond’s history before it came to England. It explores how, initially, the diamond was not a particularly desired gemstone – it sat atop the Mughal Empire’s illustrious Peacock Throne, just another treasure among the 2500 lbs of gold and 500 lbs of gemstones it featured. Yet it soon came to symbolise much more and the lure of the diamond became central to multiple power struggles, in Dalrymple words, leaving a “trail of blood and suffering” wherever it went. The diamond’s possessors were deeply unfortunate, earning its reputation as ‘cursed.’ From violent assassinations such as that of Nader Shah to the memorable tale of Ahmed Shah, ruler of the Afghan Empire, whose face was devoured by a gruesome ulcer.

The second half of the book is written by Anita Anand and recounts the story of how the British East India Company seized the diamond, along with the power of the child Maharaja, Duleep Singh. Later, he was sent to England, refused contact with his own mother and kept as one of Victoria’s ‘exotic’ princes. In one of the most memorable moments of the story, Queen Victoria is said to have shown the Maharaja the diamond now in her possession, only for him to fail to recognise it due to the extent to which it had been re-cut to meet the ‘beauty’ expectations of Western jewellery.

While the Koh-i-Noor’s story is a complex one, which takes getting your head around, helpfully there is a children’s version of the book available called The Adventures Of The Kohinoor. There is also a helpful podcast episode on it from Dalyrmple and Anand’s Empire: https://open.spotify.com/episode/5FMRc4C9R5MwITtTNuQBOs?si=eF5GKNMUQG2vgZjRrF6t9g&utm_source=native-share-menu&nd=1

Characterising the use of power

This enquiry provided a really good opportunity for pupils to unpick how power operated in a range of situations. The passing of the diamond reflected the rise and fall of various Empires and, over time, the diamond became a symbol of imperial power in its own right. Through the range of Empires pupils encounter (including the Mughal Empire, Persian Empire, Afghan Empire, Sikh Empire and finally the British Empire), pupils are able to appreciate the nature and fragility of imperial rule.

As well as the trends and overview of imperial power, there are moments of real depth for pupils to explore different methods of power used by each of the emperors to obtain the diamond and, often by extension, dominance. Some of the stories are absolutely fascinating and are gripping in themselves.

A short extract from a guided reading in Lesson 4 – What does the Koh-i-Noor reveal about the power of Ranjit Singh?

Pupils are given the challenge of describing what kind of techniques and power-play each ruler used to obtain the diamond, which varied widely from coercion and violence by Ranjit Singh to the more subtle manipulation used by the East India Company. This enables pupils to think carefully about the nature by which power was wielded by the diamond’s various rulers.

A spectrum we used to encourage pupils to characterise the wielding of power at points in the story:

Material culture angle

Something else we love about the Koh-i-Noor’s story is the opportunity it provides for focusing on ‘material culture.’ As the diamond passes from hand to hand, it begins to carry cultural connotations that only increase its value. To unravel the multiple meanings that have been attached to one physically unchanging object is at the heart of the way we want pupils to engage with cultural history. It requires them to understand that the ideas behind the actions and words of people in the past take some dissecting and contextualising to appreciate. For instance, by studying the lengths various rulers went through to obtain the Koh-i-Noor, pupils can start to make inferences about what it meant to them.

More revealingly still, we found that analysing how each of the Koh-i-Noor’s owners displayed the diamond once it was in their possession provided great insight into their ideas about it. For instance, as one of many of many gems on the Peacock Throne, the Mughals characteristically saw the diamond in terms of its artistic value. Yet when Nader Shah stripped the Throne of the jewel and wore it on an armband into battle, we can suppose he was invoking the might of the by-gone days of Mughal Empire. Ranjit Singh’s insistence that the diamond was transported in one of 40 identical camels’ pouches (should they be ambushed on their travels) might even suggest that he saw ownership of the diamond as synonymous with his legitimacy to rule. Finally, the diamond’s own dedicated room in London’s 1851 Great Exhibition brings us back round to its status as prized colonial loot…

Below is an example of an activity from Lesson 4 where pupils’ analyse a source from an old courtier through a cultural history lens to unpick what Ranjit’s actions revealed about what the diamond ‘meant’ to him

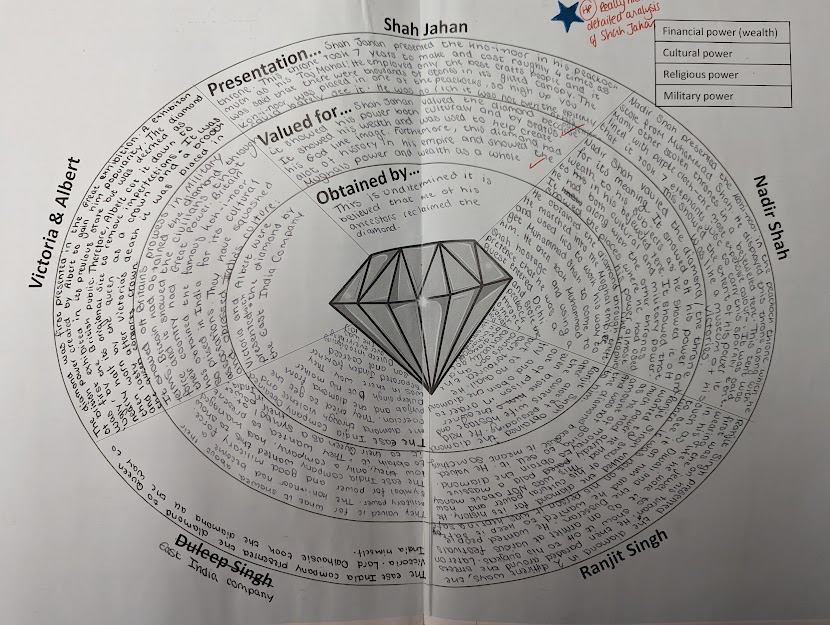

Example of overview sheet that pupils completed throughout the enquiry to record their ideas about what the Koh-i-Noor reveals about power

Aspects of decoloniality

One of the particular strengths of this enquiry is that the British Empire does not feature until Lesson 5. The richness of the Indian subcontinent and its various Empires are covered on their own terms, which challenges the narrative of ‘European Empire’ as exceptional or as a unique form of Empire. During a reading homework, which is a chapter from the children’s Adventures of the Koh-i-Noor book, pupils are exposed to the origins of the word mogul (definition: a rich or powerful businessmen) and in so doing how the British were astounded by the wealth and prosperity of the Mughal Empire when they came across it. The opulence of the Peacock throne, having cost four times as much as the Taj Mahal to build, demonstrated the power of the Mughals to Europeans at the time.

This story promotes a decolonial view in the sense that it exposes the brutal power struggle and harsh reality of British imperial rule. There is nothing to recommend the Empire in this story and certainly no balance sheet approach would be possible. Through the story of Duleep Singh and the British Empire, pupils encounter the merciless manipulation of a child of 10 years old, separated from his mother, Jindan Singh (who the British imprisoned fearing her anti-British influence over the young ruler) and forced to sign a legal document relinquishing both his territory and the diamond. Furthermore, the strangely possessive relationship between Victoria and Duleep Singh once he is taken across to England provides real food for thought.

Extract from Lesson 6 guided reading

Challenging colonial values

While researching the history of the diamond, we came across a fascinating exploration of the diamond being cut by Danielle Kinsey called “Koh-i-Noor: Empire, Diamonds, and the Performance of British Material Culture” in the Journal of British Studies (2009). We found this piece inspirational for thinking about how material culture could expose colonial power and sentiment.

Victoria, keen on showing off her new possession the Koh-i-noor decided to display the diamond in the Great Exhibition. However, the response to the diamond was lukewarm at best and was seen as a disappointment by many. The diamond was not as shiny or brilliant as many Western cut diamonds due to its imperfections and irregular shape. As a consequence, and perhaps as a symbol of their new found power, Queen Victoria’s husband, Albert ended up paying vast sums to cut down the weight of the diamond by an astounding 42% to make it shine! The huge transformation is highly emblematic of the perceived superiority of Westernised standards and allowed us to draw a symbolic parallel to the Empire’s aims of ‘improving’ and ‘modernising its territories.

Worksheet encouraging pupils to compare the diamond before and after re-cutting to think about what the shape of the cut reveals about attitudes.

Sample of pupils’ outcomes

Typically high-attaining pupil’s paragraph

The Koh-i-Noor symbolised different kinds of power to each of its possessors. For example, Ranjit SIngh went to great lengths to get the diamond. He tried everything to get it off Shah Shuja, from appealing to him to threatening him and torturing his family. Once he had the diamond, he was extremely paranoid about it being stolen, and had it kept in a very secure treasury when it wasn’t being worn. The British, however, got it in 1849 by taking advantage of the young Duleep Singh. Once Prince Albert got it, he put it on display. In 1852, he got it cut down to almost half the original size to make it fit British ideas and expectations around the “beauty” of the diamond. This shows how the Koh-i-noor was valued by Ranjit Singh for the influential power it represented because of the effort he put into getting it. He could have put that effort into taking more land, getting more followers or overthrowing other powerful people around him. Instead, he devoted the time, money, resources and troops to obtaining the Koh-i-noor. This shows how he thought that the diamond represented the same amount of power in terms of his influence and authority over people Whereas, for the British Empire it represented imperial power because it had been the property of all the powerful empires around India and the British had got it. They had it shown off in an exhibition of things they had looted from places all over the world. This exhibition was a demonstration of the extent of the British Empire, and the diamond was the centrepiece. When the diamond was cut down, it showed the British were discarding all the culture and history that the Koh-i-noor held. Additionally to Prince Albert specifically, the diamond represented reputation and status. He was unpopular among the British, due to his German background. Albert hoped that the diamond would make people like him more, and tried his best to make it look as pretty (by British standards) as he could. This led to the cutting of the diamond.

Typically middle-attaining pupil’s paragraph

The Koh-i-noor symbolised different kinds of power of each of its possesors. For example, Ranjit Singh got the power of the diamond by being ‘friends’ with Shuja and he got given the diamond after a lot of pleading. This shows that the Koh-i-noor was valued by Ranjit Singh for the power to show he is the most important person. An example of this is when he placed the Koh-i-Noor diamond on his turban and walks around the streets with it on his head (he didn’t walk around only once but many times). He was also so obsessed over it that he did EVERYTHING to make sure it didn’t get stolen. Whenever he let researchers or scientists look at it or even touch it he would always be there to watch.

Whereas, for Victoria and Albert it was another kind of power. For Albert, the Koh-i-Nooe diamond was more used to gain popularity. For example Albert created a huge exhibition called the Great Exhibition featuring art, culture, science and British inventions and obviously the diamond. But the Koh-i-Noor didn’t exactly get the reaction Albert wanted instead everyone was disappointed. This was because people weren’t used to diamonds that weren’t ‘perfect’. So the Koh-i-Noor diamond had very different uses.

Typically lower-attaining pupil’s paragraph

The koh-i-noor symbolises different kinds of power to each of its possessors of the diamond. For example Nadir Shah presented it so people can see it and he can show of how wealthy he is with the koh-i-noor in his possession .But on the other hand Ranjit Singh paid for the diamond to show off his personal wealth he put it on his turban and waited and watched the diamond get put on the turban until it was done. He also paid for an army to go and free Shah Shaja from prison. But then the East Indian company took the diamond of off a 10 year old boy and they bribed him that if he didnt give them the diamond then they would prison his mum and they intimidated the boy to sign it over and they valued it for their military power and financial power so they can be famous.

Curriculum connections

If you are interested in using the Koh-i-Noor diamond’s story in a future scheme of work it is worth noting that it has an amazing spin-off story attached. Sophia Duleep Singh, Maharaja Duleep Singh’s daughter, became a suffragette and was involved in Indian nationalism. Her story specifically offers a great opportunity to engage with a wide range of early 20th century History and explore complex forms of activism. Her sister, Catherine Singh ended up living in a lesbian relationship with Lina Schäfer in Germany and together they were instrumental in aiding many Jewish families escape during World War II.