This year we approached our Eleanor of Aquitaine enquiry differently. We focused on what Eleanor’s story has represented to different historians, and why she has therefore been presented in different ways. In doing so, we asked the question of how Eleanor’s story and character has been ‘invented’, a term which encapsulates the idea that historians are active creators of new content in their work.

As is often the case, the enquiry straddles the divide between significance and interpretations. The concept of significance shone through in pupils’ exploration of how the historians select and emphasise different aspects of the past within Eleanor’s story according to their values and interests. As such, these historians determined which parts of Eleanor’s story left the realm of the ‘past’ and entered historical consciousness. The different parts of Eleanor’s life historians featured resulted in different ‘versions’ of Eleanor being remembered. As such, the enquiry demonstrates how significance works in a disciplinary context.

Yet the nature of the historians’ writing also presented an opportunity to explore how her story is framed and presented in a way typical of an interpretations enquiry. Even where historians featured the same events, we wanted pupils to see that the way they wrote about them differed in order to emphasise their version of Eleanor. Particularly valuable in this was the chance to explore the effect that the subtleties of language and tone have on the way we understand the past.

The enquiry has proved surprisingly effective in challenging that notorious issue of pupils perceiving the past as fixed and objective. Instead, they appeared to leave with a sense of the decision-making that sits behind the history they encounter in the world around them.

We think this was achieved by exploring the context and motives of the historians, how this, in turn, affected historians’ selection and framing of evidence and by providing opportunities for our pupils to experiment with sequencing and presenting different parts of her story in the style of the interpretations they studied. This seems to have given them a stronger sense of the active and changeable nature of history which they have carried forward into subsequent enquiries.

Due to the interest in the enquiry shown when we shared some resources, we thought that we would write-up what it is we felt made the particular approach we trialled successful for our department. Although not all departments include Eleanor of Aquitaine in their curriculum, most feature an enquiry which features opposing interpretations of an historical event or individual. We therefore hope there is something thought-provoking for anyone who does, or wants to, explore an enquiry of this type.

Overview of our Year 7 scheme of work

| How has Eleanor been ‘invented’? |

| How has Eleanor’s ‘Black Legend’ been invented |

| How has Eleanor’s ‘Golden Myth’ been invented? |

| How has Eleanor’s role in the crusades been invented? |

| How has Eleanor’s role in the Great Revolt been invented? (1) |

| How has Eleanor’s role in the Great Revolt been invented? (2) |

| How has Eleanor’s relationship with her sons been invented? |

| Floating lesson – Why wasn’t Eleanor exceptional? |

1. Narrowing the focus

Helpfully, there are some very striking interpretations of Eleanor’s life on which we were able to build. We used Inventing Eleanor by Michael Evans, which provided a detailed historiography of the different ways Eleanor’s life has been presented through time.1 To keep things manageable, we selected only two of the most strongly opposing interpretations so that Year 7 could really grasp the clear-cut difference. It is a well-known difficulty of interpretations enquiries that pupils often struggle to juggle both the historical content itself along with the changing context in which the interpretation took place. We therefore hoped that, by sticking to only two interpretations, we would reduce the number of moving parts and therefore allow our pupils to become engrossed in the way in which the historians’ accounts differed. Moreover, it let pupils come to terms with the concept of contemporary values influencing the past in a way that was appropriately accessible for our Year 7’s first foray into interpretations/significance.

The interpretations in question were a Victorian account by Agnes Strickland, which Evans referred to as the ‘Black Legend’ and a range of more feminist-led works about Eleanor, including Alison Weir, Marion Meade and Helen Castor, termed the ‘Golden Myth.’2 Inspired by Rachel Foster’s enquiry on ‘What’s the story of women’s suffrage?’3, we often returned to the following timeline to illustrate the shift in what Eleanor signified to historians of each period.

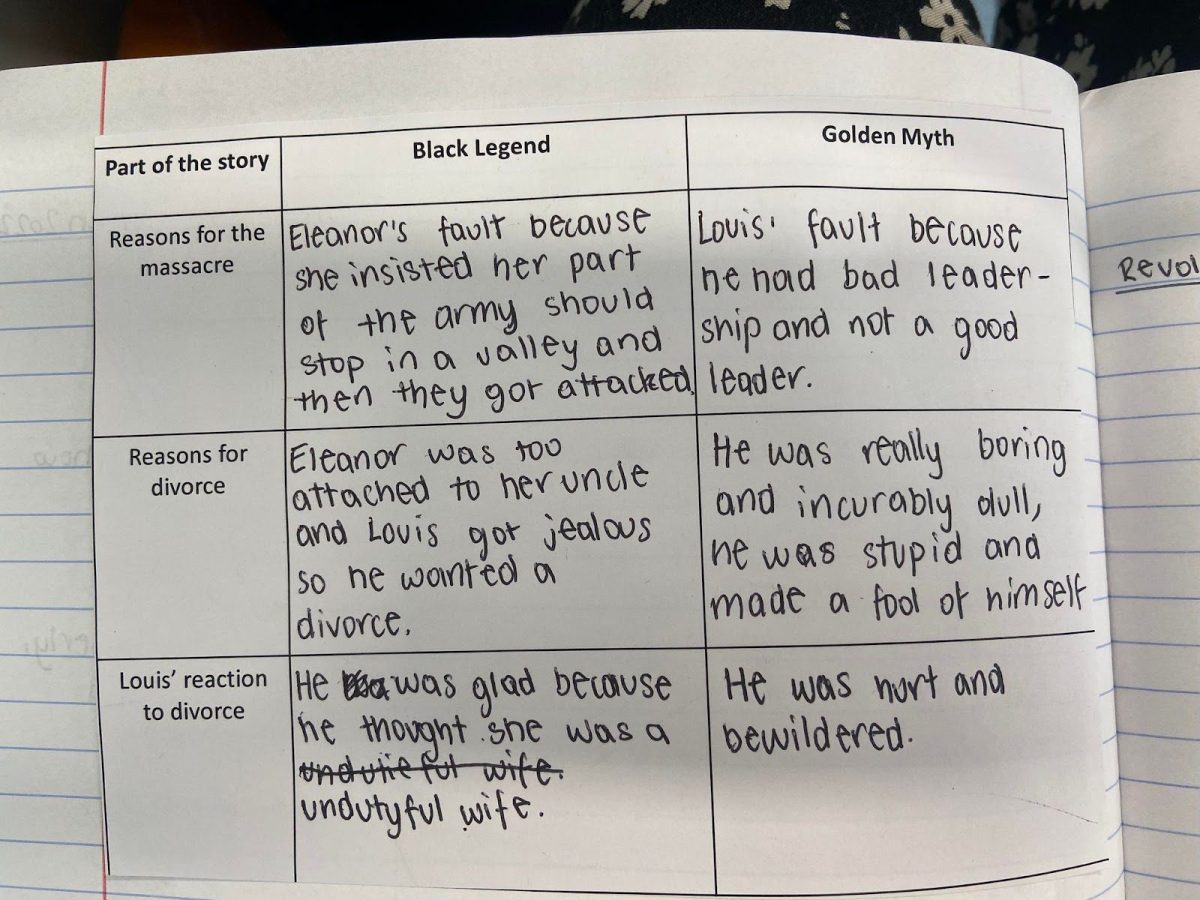

The two extracts below really encapsulate how powerfully diametrically opposed the interpretations we chose were (here the historians are commenting on the reasons for the annulment of Eleanor and her first husband, Louis’, marriage):

Black Legend: “Eleanora fell so desperately in love with him [Henry II] that without hesitation or advice she applied for a divorce from Louis, and got it. No doubt the king was glad to be rid of such an undutiful, unwomanly wife, though he did have to give up all control over his southern provinces, even Guienne.”4

Golden Myth: “Other queens had been desperately unhappy in their marriages, but they had accepted the situation, either because the prestige had made them so much better off than other women or perhaps from the feeling that husbands were lords and masters, free to treat wives as they wished.…. At her demand for a divorce, Louis was hurt, bewildered, and somewhat angry, but he still loved her and needed her.”5

2. Interpretations first

Perhaps unconventionally, we made the decision to introduce pupils to the interpretations themselves first, before teaching Eleanor’s story. We did this through two lessons exploring opposing extracts focused on her character and the very basics of her early life, at the same time exposing pupils to the context behind both interpretations. This was to keep the substantive content as simple as possible, meaning that the emphasis at this stage could be on how she was presented and the style of the historians’ writing, rather than the events of her life.

Knowing the nature of the interpretations before her story gave pupils the opportunity to immediately place new content within an argumentative framework as they learnt it. This created a closer relationship between the substantive content (Eleanor’s life) and disciplinary thinking (interpretations of her life) and avoided the issue of frontloading knowledge only to problematise it later in the enquiry. Instead, they were able to attach meaning to the new content they learnt as they encountered it.

The other key benefit of introducing the pupils to the overarching ideas of the interpretations was when we later encountered extended extracts from the historians, which were often complex (especially in the case of Agnes’ Strickland’s slightly unfamiliar Victorian turn of phrase) the ideas which sat behind them were not entirely strange or new.

3. Predictions

The other helpful aspect of using two strongly contrasting interpretations and introducing them at the start of the enquiry was that it also opened up opportunities for predictions throughout. For instance, when reading through the story of Eleanor’s escapades on the Second Crusade, pupils highlighted anything they thought would be controversial for a woman in Eleanor’s position, and therefore worthy of inclusion in either interpretation. For each highlighted example, (e.g. the many public disputes they had on the Crusade) we asked pupils what they thought a Black Legend historian might say about it and how a Golden Myth historian would disagree. This helped to highlight how the values of the different historians’ societies surrounding gender affected the historians’ presentation of Eleanor and therefore the evidence that they might choose to emphasise.

Another benefit of this approach was that by asking these questions throughout, pupils could access some of the more complex extracts as many things that our pupils predicted were reflected in the texts themselves. This was especially helpful because when they read some of the more challenging extracts their recognition of the ideas and arguments meant they could overcome complex language.

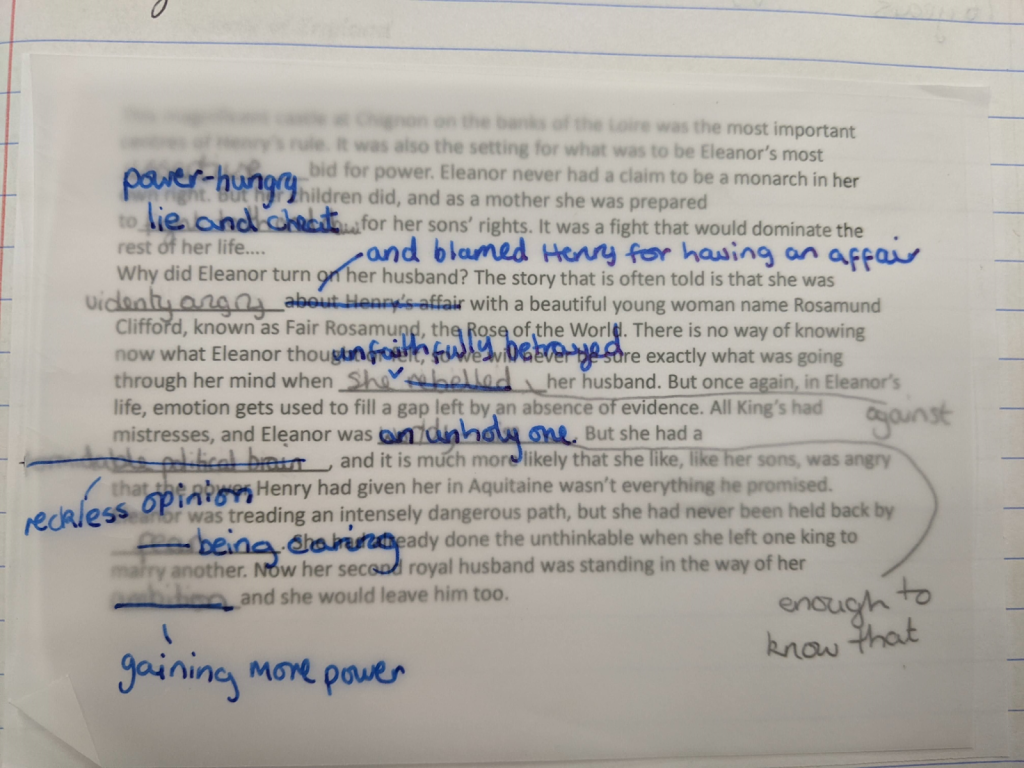

4. Framing through language

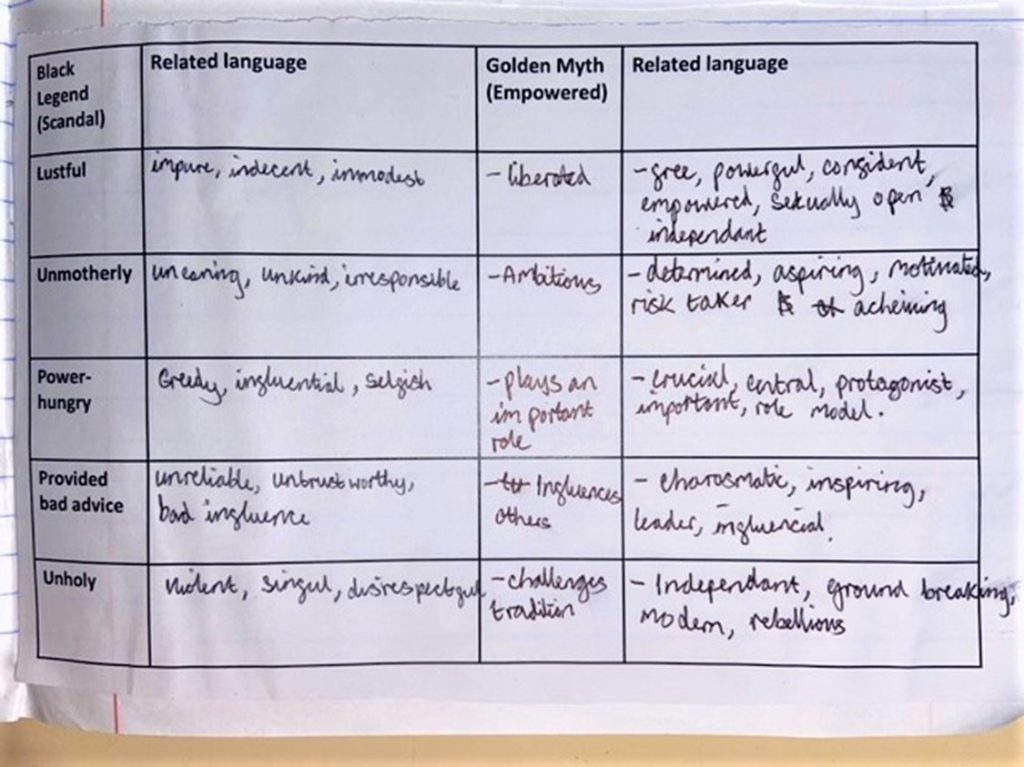

Helped greatly by the fact that the two opposing interpretations were so forceful in their nature, we repeatedly drew attention to the power of language in showing how historians framed the events of Eleanor’s life differently. In Duffy’s Devices, Ward experimented considering the adverbs and adjectives used in an extract from Duffy’s account of the Reformation to emphasise Duffy’s ‘views’ or arguments about the topic.6 We wanted to take this a stage further, by comparing the language from the interpretations to show how historians’ use of language could radically change the readers’ perception of Eleanor. Whilst planning the enquiry, we scanned the interpretations to look for the kind of key themes that would be helpful to draw out through the explicit pre-teaching of vocabulary. Therefore, at the start of the enquiry we taught pupils the language most closely related to the Black Legend/Golden myth interpretations by providing them with key adjectives associated with each view. For example, when Eleanor does not meet the expectations of a medieval woman she is, according to the Black Legend account, ‘scandalous, lustful, unmotherly, power-hungry and unholy.’ Whereas, according to the Golden Myth, these same transgressions show an empowered woman who is ‘liberated, ambitious, influential and challenges tradition.’

When introducing this language, the first thing we asked the class to do was generate their own synonyms for each word. The reason for this was to enable pupils to make links between new language and ideas with their existing vocabulary, thus securing a deeper understanding and creating a wider repertoire of words with which to discuss the interpretations. Through this, the language provided a window through which to see the stark contrast between the interpretations and, as such, the linguistic provided a scaffold to the conceptual.7

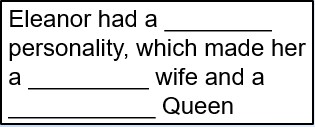

Pupils had the opportunity to put this language into practice, using the new language to fill the gaps in the sentence below, once as a Golden Myth writer and once in the style of the Black Legend.

Another way we drew attention to the importance of language in the construction of Eleanor’s life was an activity in which pupils actually changed a Golden Myth interpretation to a Black Legend one. Inspired by Christine Counsell’s example of CV Wedgewood’s account of Charles’ execution in which pupils rewrote a subordinate clause to change the tone, we asked pupils to alter a transcript of a Golden Myth documentary by changing key phrases on a piece of tracing paper.8 We found the value in the tracing paper lay in the fact that it allowed pupils to see both interpretations by flicking it back and forth. As a result, they could see that, whilst the content may remain the same, the decisions historians make about the language they use to portray it has a dramatic effect on the way an event or individual is remembered.

5. Selection and sequencing

We developed the idea of illustrating how history is constructed by using the metaphor of a ‘filter’. We illustrated this using the image of a filter with several blocks representing the different events that could have been included from Eleanor’s story in historical accounts. The idea of the filter was that it represented the historical process whereby historians can make decisions about whether to include or filter out any evidence that does not support their argument. Those events which pass through the filter are selected and written into history. This helped our pupils to consider historical significance by getting them to consider the necessary role of selection and sequencing in the act of remembering — how different parts of Eleanor’s story have been chosen and retold because they resonate and reflect different values at different times.

To help pupils wrap their heads around this for the first time, we used an analogy of their history teacher writing a book about their time working at Sawston. If, in this book, they covered lots of different experiences, but never once mentioned Year 7 as a year group, what would they suppose their teacher thought of Year 7? Most suggested, ‘they didn’t like Year 7’, ‘they didn’t think Year 7 were interesting’ and one even suggested that ‘Year 7 weren’t significant to them.’’

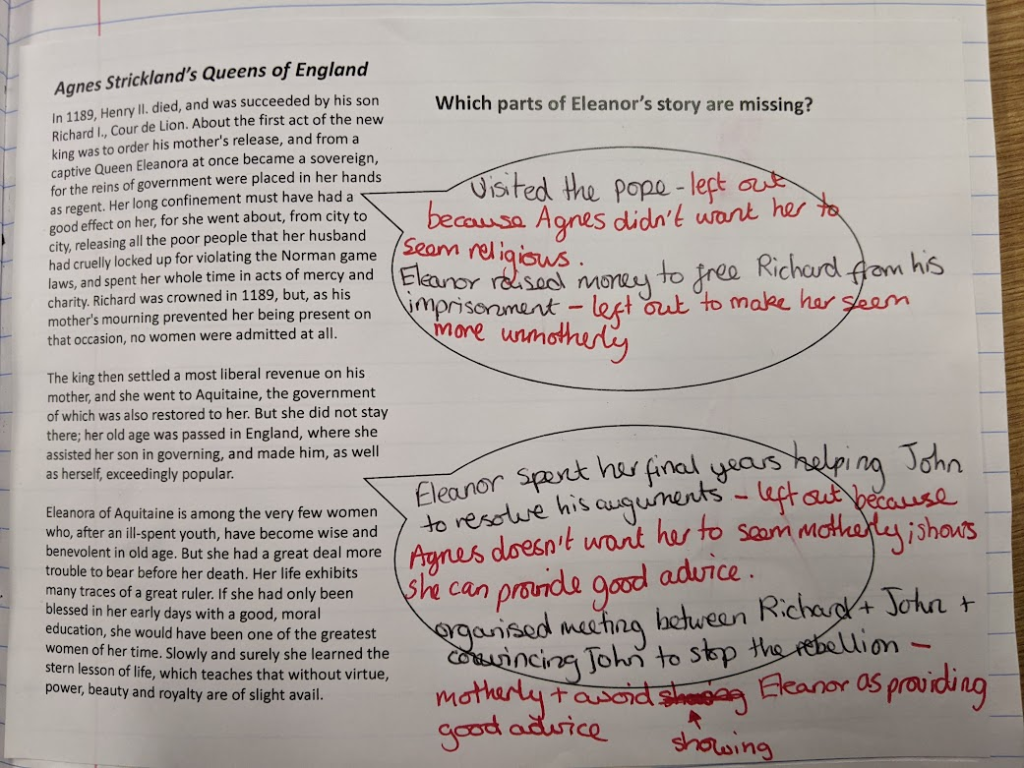

In Lesson 6, we extended this idea through another form of prediction task by asking pupils to suggest which elements of Eleanor’s final years might have been left out by a Black Legend historian and why. Following this, we looked at a real Black Legend extract and recorded which parts of Eleanor’s story had, indeed, been silenced and what these gaps revealed about the aims and ideas of the writer.

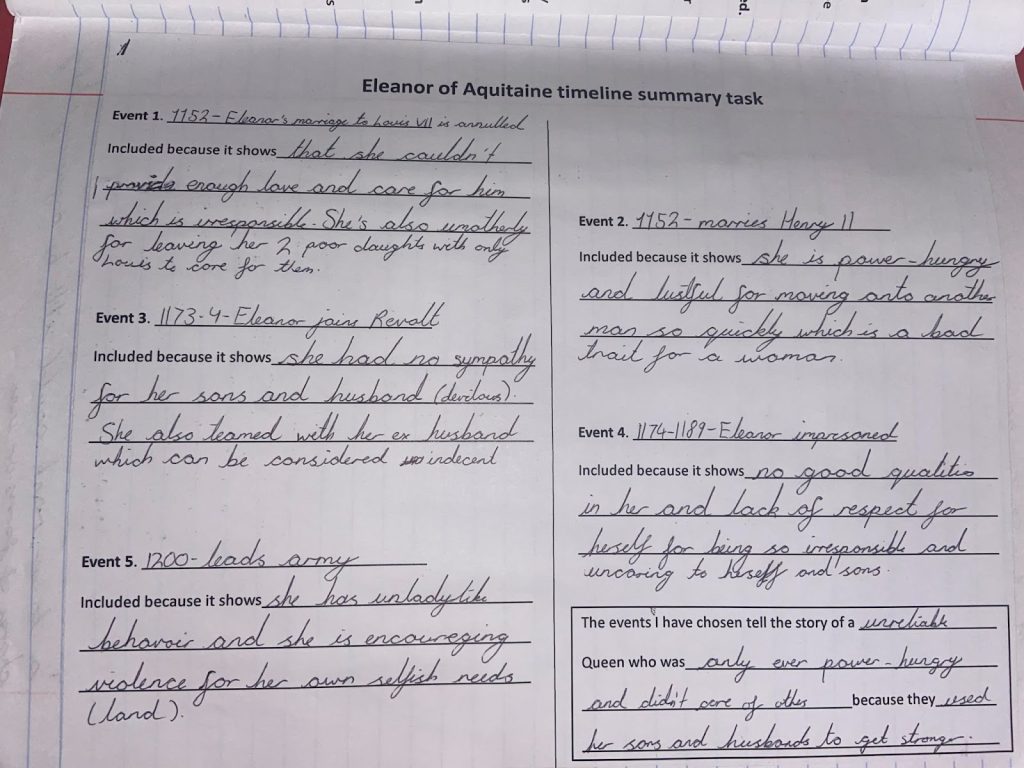

For the final outcome task, pupils created their own timeline of Eleanor’s life from the perspective of either a Black Legend or Golden Myth historian. To do this, they picked 5 events to feature out of all those they had studied and justified their place on the line by explaining why these aspects of Eleanor’s story carried significance to their type of interpretation. This, we felt, gave us a strong sense of whether our pupils had understood their chosen interpretation by testing what they think would pass through ‘the filter’ and where tactful silences might be created.

6. Tackling exceptionalism

One of the issues we had when teaching our old enquiry on Eleanor was that pupils left thinking Eleanor was exceptional in her power and achievements. The problem with this is that, in order for Eleanor to be ‘exceptional’ every other woman has to be downtrodden and without power or prospect.

Of course, it is true that Eleanor was exceptional in many respects and that her particular circumstances makes her story stand-out as especially noteworthy. Yet, we know that women were able to challenge traditional gender roles in a range of contexts as shown in Eileen Power’s book Medieval Women.9 One way we aimed to demonstrate this was through a ‘Meanwhile, Elsewhere’ on Queen Melisende who was able to challenge gender expectations, also through her involvement in the Crusades.10

Secondly, we asked pupils to use examples from Power’s book to reframe misconceptions that some people might have about Eleanor being entirely atypical. The takeaway from this was that, even if less publicly, women have asserted their influence within their own spheres and contexts just as successfully. While this was only one lesson (which could come anywhere in the second half of the enquiry), we hope we illustrate examples of other ways in which women have challenged traditional gender roles throughout our curriculum in a way that will show rather than tell that Eleanor was not entirely exceptional in this regard.

Conclusion

As an enquiry, this was immensely enjoyable to teach. The opportunity to get into the nitty-gritty of why historians present competing versions of the past and how felt really valuable for our Year 7s. Moreover, the story of Eleanor contains so many memorable stories that pupils were able to keep track of the substantive and conceptual notably well. Whilst we can only say that this approach worked well for us in the context of our school and curriculum, we hope we have shared some approaches and ideas that others may find helpful in their own interpretations/significance based enquiries.

Footnotes

- Evans, M. (2014). Inventing Eleanor: The Medieval and Post-Medieval Image of Eleanor of Aquitaine. City. Publisher.

- Castor, H. (2010). She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled England Before Elizabeth. New York. Harper Collins; Weir, A (2000). Eleanor of Aquitaine. New york. Ballatine; Mead, M (1977). Eleanor of Aquitaine: a Biography. New York. Hawthorn Books.

- Foster, R. ‘What’s the story of the women’s suffrage campaign?’ https://www.suffrageresources.org.uk/activity/3209/whats-the-story-of-the-womens-suffrage-campaign

- Kaufman, R. (1882). Agnes Strickland’s Queens of England, Vol. I of III, Abridged. Boston: Estes & Lauriat

- Mead, M. (1977). Eleanor of Aquitaine: a Biography. New York. Hawthorn Books.

- Ward, R. (2006), ‘Duffy’s devices: teaching Year 13 to read and write’, Teaching History 124

- Woodcock, J. (2005) ‘Does the linguistic release the conceptual?’, Teaching History 119

- Counsell, C. (2003) ‘Who cares about Charles I? Cunning Plan for a Year 8 lesson on C.V. Wedgwood’s writing’, Teaching History 111

- Power, E. (2012), Medieval Women. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Meanwhile, Elsewhere on Queen Melisende by Chelsey David https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Yo4ZeSAhGyoxfW6RFDgpy4A2XwI_eVBg/view